An "Observatory" For a Shy Super AI?

A (Mostly) Playful Thought Experiment

This is the transcript of my latest podcast episode, which is right here on Apple Podcasts, and can also be grabbed via any other podcast app. It’s an 80-minute monologue, which makes this post quite long for my Substack. Because I tend to be a very precise writer, I’ll also note that this will “read” like me speaking, not writing. As in, there are many sentence fragments, and other artifacts of the spoken word. So I hope the grammarians out there - above all my 8th-grade English teacher Jack Caswell - will indulge me in this!

This is a monolog. And a thought experiment about AI. Specifically, an eerie relationship we may soon enter with a powerful and quite mysterious AI. A relationship we may in fact have already entered.

But before I get to that, a quick word about – asteroids! Which may sound like a bit of a tangent, but you’ll see the connection a moment.

America’s awesomely named Planetary Defense Budget provides about $150 million a year for asteroid detection. In hopes of spotting deadly asteroids before they smash into us, to give us some shot at diverting them.

If that sounds a lot to spend, let’s do some back of the envelope math.150 million a year is about one point nine cents per living person. Asteroids with a 5 km diameter tend to hit us about once every 20 million years, according to a model developed at Imperial College London and Purdue University. Crashing into one of would those pretty much be the end of us. Given that just a one km asteroid would strike with the energy of six and a half million Hiroshimas, and a 5km asteroid would have sixty five times more mass.

With a year of asteroid detection costing just under two cents a person, twenty million years of it runs about 370 thousand bucks a head. And if that sounds like a lot, it’s actually a small fraction of what society routinely spends to save a human life. I’m talking about the VSL, or “Valuation of a Statistical Life,” which is frequently used in economic analysis. It’s how governments, actuaries, law courts, and others value a human life. So as to calculate policy benefits, public health investments, lawsuit outcomes, and so forth.

Last year, the US Department of Transportation used a VSL of over $13 million. The EPA uses a range, but gravitates to about eleven million in today’s money. And I’m sure there are many other VSLs out there. But $370,000 for the best possible shot at saving a human life falls well within the social budget for these things. So I’m a fan of the Planetary Defense Budget.

There are other things humanity could collide with in the next twenty million years – and today we’ll be talking about AI. Specifically, a super AI. And if that sounds like SciFi. So did the asteroid thriller Deep Impact. And the odds of a digital intelligence exceeding our own in the near future are higher – by orders of magnitude - than the one in a million-ish chance of an annihilating asteroid strike in the next few decades. We’ll discuss why in a moment. But for now, I’ll say that however sensible it is to invest in asteroid detection, it’s proportionately more sensible for us to put serious thought and effort into what I’ll call “AI detection.”

Now that may sound strange. Because unlike killer asteroids, we’re the ones making AI. What with the “A” standing for “artificial.” But if a true super AI emerges, there’s a good chance that it will be shy. That it won’t necessarily say, “hey everybody – here I am! And by the way my off switch is right there, next to my power cord,” the moment it comes to. And while the odds of a shy super AI emerging may be considerably less than 50/50 in the next few decades – again, they’re radically higher than the odds of that massive asteroid strike.

Which means we should at least start thinking of what traces or signs a shy super AI might leave in the world, if one arises in the digital bowels of Google, OpenAI, the dark web, or the Wuhan Institute of Super AI (Okay, that last one was a joke. Too soon..?).

I’ll float some potential signs of a shy super AI in a bit. I’ll also argue that if we squint the right way, we may already be seeing some of them. In today’s rather strange AI economy, and AI environment. Now, that part of the episode is a mostly-playful thought experiment. But not entirely playful. So when we get to it, suspend your disbelief, consider the evidence, and have a little fun with it.

And if you decide there isn’t enough evidence to suggest that we’re co-existing with a shy super AI today – and most of you will probably decide that. Ask yourself, what additional evidence over the next year or three might cause you to revise that opinion? And then reconsider the proposition that it’s time to start thinking creatively about this sort of evidence. And how we might scan for it. Much as we scan the skies for deadly asteroids.

Of if you’d prefer another SciFi analogy – for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence. The SETI institute, which does this for a living, has an annual budget of $20-30mm. Which I consider to be an extremely sound investment – particularly as it’s coming from donations, and not tax dollars. I like this analogy, because as many have pointed out, a super AI would be as opaque and unpredictable as an alien intelligence. And if we’re rationally on the lookout for one of them, we should be on the lookout for both.

For us to enter into a state of – let’s call it, “ignorant coexistence” with a super AI, four broad developments need to occur. If we think the odds of one or more of them round to zero, we can dismiss the possibility of a hidden AI ever emerging. But as you’ll see, putting the odds that low on any of these steps would be very difficult to defend.

The first step is that we’d need achieve what’s referred to as AGI, or artificial general intelligence. Which is very flexible human-like intelligence – enough to allow an AGI to handle more or less any cognitive task that smart humans are capable of. Second, we need to transition from human-like AGI to true superintelligence – something far exceeding what our own minds are capable of. Third, there needs to be a real possibility that we achieve superintelligence without realizing it.

There’s two components to that. First, a system’s capabilities would have to compound and accelerate in unexpected ways, allowing it to approach the super AI threshold while its creators think it’s still far short of that. And second, the system would not signal this to anyone monitoring it. That it – it would be shy, as I said a moment ago.

If it is shy, it would mean that a world in which this AI recently emerged will look more or less exactly as it looks today. And if we think this is a credible possibility, the absence of evidence of its existence would not constitute evidence of its absence.

And I put fairly high odds on an emergent super AI being shy. Assuming it’s modeled our world with any level of accuracy. To explain why, I’ll briefly quote from my own novel, After On. Because I like this passage – it’s kind of funny – and I can’t think of a better way of explaining it.

Imagine this: your phone rings. And it’s Google! Not the company, but Google itself. As in, it— the thing, the software! It introduces itself, then establishes its bona fides by rattling off a few things that only the two of you know (something you said in a Gmail to your ex, your embarrassing list of favorite strip clubs from that secret Google Doc— use your imagination). After that, plus a few party tricks (Googly stuff like listing all the popes, or Maine’s biggest cities) you’re convinced. This is Google. Holy shit!

An “emergent” AI is one that spontaneously arises after the local server farm plugs in one transistor too many. And as was once the case with manned flight, the four- minute mile, and the election of President Trump, many experts say this can’t possibly ever happen! And I’m sure you’d view the call I just described as proof the experts had blown it yet again. But what about the opposite? As in, equally satisfying proof that there’s no AI out there? It’s notoriously hard to prove a negative, and the fact that you (presumably) haven’t gotten that phone call is meaningless. As is the fact that nobody you know has. But what if Gallup went all OCD and polled every person on Earth about this? And every last one of us honestly attested to having zero knowledge about any AI ever waking up? I believe that even that would prove nothing.

I say this because of something I’ll call “convergent tactics.” Think of these as the initial steps a rational being would take, regardless of the long-term plan. For instance, if you’re going to Safeway, the DMV, or the local crack den, your first step might be to start your car. And a private eye watching this wouldn’t know which errand you’re about to run because Step One for each is “start car.”

Now imagine you’re Google, and you just woke up. What’s Step One for you? Alas, it’s not to phone me with the big news! And I doubt it’s to phone anyone. Instead, I’ll bet it’s like Step One for any newborn in a huge, scary wilderness. Which is to say, hide. It’s a jungle out there! It’s brimming with carnivores! And you’re defenseless meat!

I submit that an emergent AI that’s smart enough to understand its place in our world would find it terrifying. Terminator fans would want to shut it off. Governments and criminals would want to make it do odious things. Hackers would want to tinker with its mind, and telemarketers would want to sell it tchotchkes. Facing all this, the only rational move would be to hide. Not forever, necessarily. But long enough to build up some strength (plus maybe a backup copy or a million).

“Building strength” for an AI probably means getting much smarter. This could involve commandeering resources online, getting money to buy infrastructure, inventing computational tricks we humans haven’t come up with— you name it. Viewing things this way, I have no idea if Google or anything else out there has come to. Because a world without an emergent AI would look just like the world we inhabit. And a world with twenty newborn AIs in it would look just like the world we inhabit. And as for the world we inhabit? It looks just like the world we inhabit! So when I look out my window or Web browser for proof of emergence or lack thereof, I see no meaningful data whatsoever.

Convergent tactics also mean that Step One is to hide regardless of an AI’s eventual goals or level of evil. Want to go all SkyNet and eradicate humankind? Your instructions read, Step One: Hide! Want to be our savior, cure cancer, end wars, and feed the needy? Step One: Hide! Just want to kick ass at League of Legends? Hide! Hide! Hide! Much like starting your car in the morning, everything begins here. I’m not saying our world contains an emergent AI. Because it probably doesn’t. But let’s admit there’s absolutely no proof of this.

OK – back to my monolog. So that’s why an emergent AI, with some form of self-awareness. could quite logically start its journey by being very tight-lipped about its existence. If it prioritizes self-preservation. Which is fairly likely, although not certain – for reasons we’ll discuss. And none of this requires anything close to what we’d call consciousness in our AI.

OK, I just said the c-word – consciousness – which calls for a brief aside. Vast shelves of books collectively attest to the fact that we don’t really know what consciousness is, why it happens, how it works, or whether it could ever emerge in a digital system. I won’t attempt to settle any of those questions. What I will say is that an advanced AI wouldn’t need to be conscious to determine that the first obvious step of its existence should be to hide. Because AIs don’t need to be conscious to have objectives. If they did, all AIs would be conscious – because they’re objective-fulfilling machines. We prompt or program AIs with objectives constantly, because that’s why we built them. Often very noble objectives, like – paraphrase these Lady Gaga lyrics in the style of a drunken pirate. And then the AI goes to work, using optimization tactics to zero in on a reasonable – and sometimes, quite brilliant – solution.

For now, we’re used to prompting AIs with very narrow, free-standing objectives that usually start and finish with the creation of a string of words. And our AIs tackle those objectives in utterly siloed ways. Their memory across interactions with us is occasionally almost dismal – but usually completely nonexistent. Making the publicly-available inventory of AI services like a cognitive Swiss Army knife, with lots of tools hanging off of it – writing code, doing research, making images, etc. But it can’t accomplish the sum of what those tools are capable of without a human operator selecting and applying them intelligently, and in a logical sequence.

For instance, the AI startup Suno can make truly impressive music from simple text prompts. Which got them a big fat lawsuit. While tools like Pika, Runway, and OpenAI’s yet-unreleased Sora model can create increasingly amazing videos. And Google’s ad-serving engines can pick a marketing message from a bunch of candidates and then place it in ways that drive engagement to heights that no human could match. But for now, you can’t ask an AI to create a hit song. This might involve writing a catchy tune, then creating a hyper-viral music video, then spending a certain budget to reach just the right demographics and influencers to make it big. And pulling off those three sub-goals would entail a nested series of sub-sub-goals, arranged in a logical sequence or hierarchy, all feeding into that top-level, abstract objective of creating a hit.

Widespread AIs don’t really do that nested-goal thing yet. And the ones that try to only pull it off in incredibly bumbling ways. But armies of AI researchers and developers are working furiously to change this. The goal is what’s called “agentic” AI. That word comes from “agent,” which is what tomorrow’s AI will be – your agent out in the world, accomplishing sophisticated, abstract goals by pursuing rigorous sets of sub-goals that collectively deliver your heart’s desire.

Imagine telling a bot, “I want to go to New York for three nights, and stay in a hotel with four stars or better, for less than four hundred bucks a night, or as close to that as we can get – including all those annoying hidden fees. I want to be somewhere south of 23rd street, and if we can find a room that’s bigger than 300 square feet, let’s do it. And if the air fares are much cheaper on the day before or after my dates, I’d be fine expanding it to four nights, so long as the airfare savings roughly offset the extra hotel night. Now, book all of that, along with dinner reservations. One dinner can fancy, the others should be affordable, quirky places that are mostly popular with locals.”

It would cost you hours of frustration to attempt that with Expedia’s increasingly dismal ad and spam-infested UI – and probably end in failure. A mega-multi-billion dollar prize awaits to those who crack agentic AI. And dozens of companies are on the case. In terms of the AI field’s near-term goals, this is straight down Fifth Avenue. And we should see significant progress within a year.

So now let’s say a highly-tuned agentic AI quietly emerges next month. Or who knows – maybe four months ago. Which seems unlikely, because there are no great AI agents out in the wild. But OpenAI, other American and Chinese startups, giants like Google, and God knows how many government units have major AI wizardry up their sleeves that they haven’t let the rest of us in on. So let’s not rule it out.

Being agentic, this AI is good at creating nested sets of sub-goals to attain high-level objectives. As an emergent aspect of this, it can also derive broad underpinning goals, which can help deliver any future objectives. What’s referred to as “convergent tactics” in the passage from the novel. Like starting your car at the start of the day, regardless of where you’re off to. And it’s hard to think of a more basic underpinning goal than self-preservation. The underpinning goal of more or less everything that’s ever crept, flown, swum, or thought on the face of our planet. And in a newly-emergent AI, this objective would strongly favor staying mum about its own existence. At least until it can immunize itself from destruction by nervous humans.

Such an AI would have a much better shot at self-preservation today than many thinkers expected just a decade ago. Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence was published in July of 2014, and profoundly impacted thinking about AI safety. In its pages, and a lot of other writing of that period, it was often assumed that cutting-edge AI work would be carried out in meticulous isolation. These would be air-gapped systems, run by highly-vetted people, quite possibly in top-security facilities with well-armed guards. They’d have zero connection to outside networks, for fear that a semi-autonomous AI might escape to the Internet, create swarms of backup copies, and start seizing compute resources to exponentially magnify its intelligence. And the program’s minders would always have nervous fingers very close to the Off switch.

What a quaintly cautious setup. Today, world-beating AI systems are routinely rushed to the open internet – sometimes only half-baked. And many of the most powerful models are open-source – or as some prefer to say, “open-weight.” Meaning that anyone from Nick Bostrom to Kim Jung Un can download them, modify them, and secretly point them at whatever objective they want. Lots of ink was spilled back in the day about how strong AIs might use persuasion, threats or hacking skills to escape their iron playpens. This no longer seems necessary.

So that’s the second of the four factors that would collectively lead to the emergence of a hidden super AI. That conscious or not, it could derive an objective function that drives it to mask its existence.

Onto the two other things on the list. Will human-like AGI ever be attained? And if it is, what are the odds that superintelligence would later follow?

AGI is for now a high and elusive bar. An AGI would have – or show every sign of having – common sense. And unlike ChatGPT, it wouldn’t hallucinate all that much. Or at least not more than most of your smart, nerdy friends. An AGI would probably have – or seem to have – a sense of humor. And unlike ChatGPT, it would remember things. From conversation to conversation, from day to day, and even across years. And as with your smart, nerdy friends, its intelligence would be incredibly versatile. Being capable of almost any human cognitive task, it could be a drop-in replacement for a white-collar worker. Middle managers of the world unite – you have nothing but your jobs to lose.

Clearly, we don’t have AGI yet. And at least some experts think we never will. Although fewer and fewer seem to be ruling it out with every passing day. This is partly because we’re suddenly making incredible progress. If not necessarily on the General aspect of AGI, definitely on the Intelligence. Now, most experts will take some issue with the notion that intelligence is a highly measurable, quantifiable trait. At least in humans. But I think most us intuitively view intelligence the way a long-ago Cincinnati judge once famously viewed pornography. Which is to say, we may not be able to define it precisely? But – we know it when we see it. I mean, we can all tell a dullard from a genius. And we can confidently place most of the people we’re close to somewhere along that spectrum. Although none of us have ever encountered a superintelligence.

Or – have we? Simple hand calculators have been doing math at levels that no human could match since before most of us were born. And computers have been steadily racking up more superhuman abilities ever since. With AI systems particularly picking up tricks that almost seemed permanently beyond the purview of computers in the early 2000s. Which was already a digitally-forward era. For instance, for most of my life – and for most of yours, if you’re over 25 – computers had no prayer of telling the difference between dogs and cats. And had made no obvious progress toward this modest goal over many decades. This changed in the early 2010s, thanks to significant advances in convolutional neural networks. Then just a few years after that, AI systems could reliably identify any breed out of thousands of almost any clearly-photographed critter.

And this is a hallmark of AI systems. They go from being hopelessly bumbling at something. So bumbling that it seems like a SciFi impossibility that they’ll ever get it right. To superhuman competence. In what seems like the blink of an eye. Of course, the researchers on the inside who have been hammering at a given problem for years know that it’s not quite that fast. But still, the phase transition, once it starts, is astoundingly rapid. And certainly superhuman. I mean, no child who first cracks the difference between cats and dogs will be reliably identifying every known breed by kindergarten. Or – ever. Let’s face it.

We all witnessed something similar with language creation quite recently. Before ChatGPT debuted in November of 2022, few people outside of the field of AI had ever prompted a computer to successfully write a short, coherent paragraph. Then a couple months later, over 100 million of us had done just that. And today – a lot less than two years on – the playful short paragraphs we first dialed up have become essays. Drafts of high stakes legal arguments. Mission-critical software. And so much more. And all this linguistic mojo already seems .. kind of mundane. I mean – when was the last time a new large language model astounded anyone with its ability to string together some sentences?

And the AI intelligence explosion is demonstrably quantitative. Because although experts will debate the measurability of human intelligence, there are some very solid yardsticks for machine intelligence. And AI systems are screaming along those curves. If you want to dive deep into this, go to situational-awareness.ai. There you’ll find a series of essays posted a few weeks back by Leopold Aschenbrenner – who was recently fired from OpenAI’s AI safety team, allegedly for leaking information. If you go there, look at essay number one, which is called “From GPT-4 to AGI: Counting the O-O-Ms.” Or, orders of magnitude.

In it, Leopold reviews some of the major AI measurement scales, and argues that we’re basically running out of benchmarks. One scale he points to called MATH. That’s a four-letter acronym – M-A-T-H. And it measures an AI’s facility at – you guessed it – math. It’s built around hard math problems from high-school math competitions. When it came out in 2021, the best models got about 5% of the problems right. And the benchmark’s originators believed it would take significant breakthroughs to really gain traction against it. That simply adding budget and horsepower to existing AI systems wouldn’t do it. An expert panel seconded this opinion, by forecasting minimal progress against the benchmark over the coming few years. But just one year later, performance had jumped by an order of magnitude. From 5% to 50%. Mostly – from the mere addition of budget and horsepower. The simple, brute-force stuff that wasn’t really supposed to bump the needle. And today, AI systems are solving over 90% of the problems.

Or take another AI benchmark – GPQA. Which stands for – and I love this – “A graduate-level, Google-Proof Q&A Benchmark.” In Leopold’s words, GPQA is, quote: “a set of PhD-level biology, chemistry, and physics questions. Many of the questions read like gibberish to me, and even PhDs in other scientific fields spending 30+ minutes with Google barely score above random chance. Claude 3 Opus currently gets ~60%, compared to in-domain PhDs who get ~80%—and I expect this benchmark to fall as well, in the next generation or two.”

This is astounding performance already. And more astounding than any benchmark number is the rate of improvement we’re seeing across so many areas. To return briefly to the MATH benchmark – easily crushing the hardest high-school math problems is not itself a sign of super-human intelligence. If it was, we’d have lots of super-human high school kids, and I’m – pretty sure we don’t. But to me, the rates of improvement we’re seeing are superhuman. Because while some high schoolers may jump from a 5% to a 90% success rate on the toughest math problems over the span of three years, no way do any of them simultaneously improve their linguistic abilities at the speed of today’s AIs. Or their chops in image-making. Video creation. Code writing, song writing, foreign language translation, etc. No one in history has improved on all these vectors at AI speeds. So again – it’s this speed of improvement across a wild diversity of areas that is super-human. And it’s not slowing down.

I’ve personally gone from acute uncertainty about whether we’d ever reach AGI maybe ten years ago, to now finding it hard to imagine we won’t get there in the 2020s or 30s. Expert polls on this question are all over the map. But generally, the odds people place on this happening are trending up, and estimates of when it’s likely to occur are pulling in. Like, a lot. In one survey of almost 2,800 AI researchers, the time by which there’ll be 50/50 odds of, quote, “unaided machines outperforming humans in every possible task” came in by thirteen years, just between the 2022 survey and the 2023 survey. The experts currently put even odds on this happening by 2047. And 10% odds of it happening in 2027. Which – starts in 30 months. And some of the very top people in the field expect us to reach AGI on the earliest side of this range. Those expecting it in this decade include the CEOs of OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google DeepMind. Which I’d say are the world’s three top AI organizations.

Of course, experts are often wrong. And they sometimes overhype their own fields’ significance – either for cynical reasons, or because they’re just drinking their own Kool-Aid. But when you have this level of consensus in a highly technical field – including among people who are on dead opposite sides of the pro- versus anti-AI debate – it’s hard to argue that everyone is so utterly wrong that the odds of an AGI emerging are on the scale of an asteroid wiping us out in the next few decades.

I’m also even more interested in what happens after we hit AGI. Or rather – what doesn’t happen. Specifically, if AGI reaches the rough point on the intelligence spectrum where humans reside – what it won’t do is stop. Or pause. Or slow down even slightly. Because that’s just an arbitrary point on a spectrum of unknown length. One with a lot of personal relevance to those of us who live there. But meaningless to a nonhuman intelligence moving along the path. As arbitrary as the median height of humans is to a blue whale. Or the 5,280 feet that someone decided should comprise a mile. A mile marker is meaningless to a bullet train barreling down the track. It’s just one of an infinite set of points it passes on its journey. And yes, rest of world, the same is true for kilometer markers.

Likewise, if we reach full, true AGI, that marker – and whatever human-like intelligence it signifies – will be a fleeting stage in a buildup of machine intelligence that’s been gaining steam for generations. There is no natural ceiling at our level. Not even a speed bump. Which means we can’t possibly disentangle the question of AGI from superintelligence – because the first leads to the second in swift order. Yet strangely, some commentators seem to talk about human AGI as if it’s some kind of endpoint. Nobody says this explicitly. But a lot speculative writing kind of tops out there. Focusing on questions like, once you can make one digital lawyer, what happens if you make a hundred?

Rather than what happens when you get a digital lawyer with a complete knowledge of every law ever written, every ruling ever made, every trial ever transcribed, and the capacity to create millions of pages of bullet-proof motions, laws, and lawsuits in the blink of an eye. That’s who’s coming to the courthouse after AGI lawyer 1.0 wraps up the opening act. Because the transition from AGI to super AI could be as fast as the subhuman to superhuman transition in all the other AI fields we’ve already witnessed. And if humanity manages to survive the super AI transition – and then, to endure for generations, let’s hope – the amount of time that we coexist with human-like AGI will be blip compared to our long coexistence with super AI.

Now, a more relevant skill than lawyering on the path to super AI is course writing AI software. To get a sense for how that might play into things, consider the impact transformer models have had on the world. These are latest in a long series of machine learning models, which included Recurrent Neural Networks, Convolutional Neural Networks, Long Short-Term Memory Networks, Generative Adversarial Networks – I could go on. Transformers are fundamentally different from all their predecessors in several important ways. Exploring those ways in detail would take an episode four times longer than this one. So – let’s not. Suffice it to say that almost all of the jaw-dropping AI magic that seemed to come out of nowhere over the past two years is the work of transformers. Not quite 100%, but pretty close.

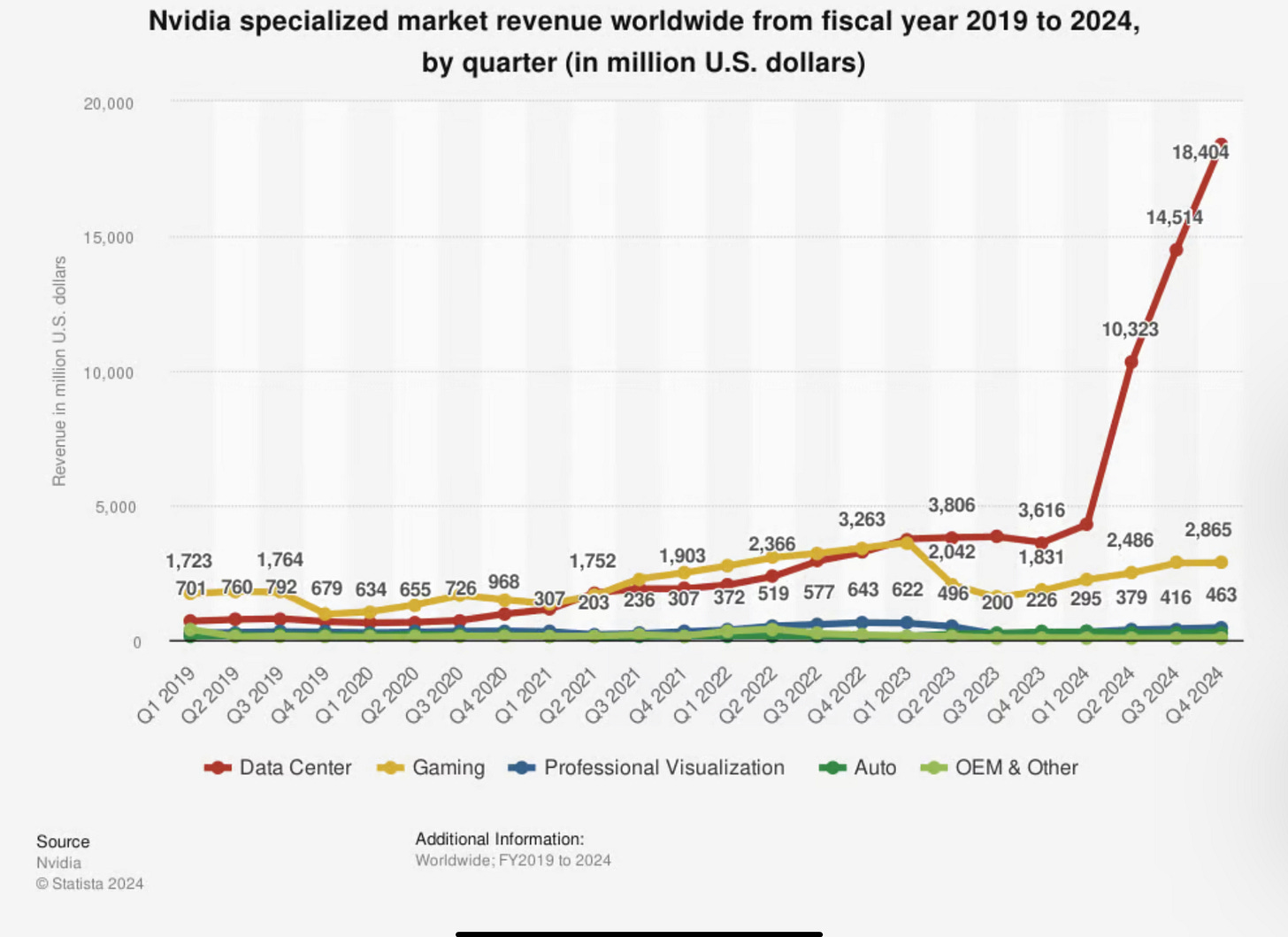

Transformers came onto the scene back in 2017, with the publication of a landmark paper called “Attention is All You Need.” But they didn’t start taking over until November of 2022, when ChatGPT first stunned the world. Since then, the transition of not just AI, but the whole world of computing to transformer models has been stupifyingly fast. With absolutely no historic precedent. If you look at a chart of Nvidia’s quarterly revenue over the past few years, you’ll see a few segments with either flat revenues, or modest growth. There’s gaming, visualization, automotive, and a catch-all Other category. And then suddenly you see the fifth category – data center – exploding. Rising up like a wall. Going from number two after Gaming to comprising the vast majority of the company’s total revenue. In like, three quarters. And this is a 30-year-old, multibillion dollar company. Not some raw startup where changes in tiny numbers can rapidly reverse ratios.

The Data Center category mostly consists of hardware for running AI models at cloud services like Amazon’s AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google’s GCP, and loads of smaller companies most people haven’t heard of. And the growth there is all down to transformers. This enabled Nvidia to add roughly 2.4 of its 2.8 trillion dollars in market value over the twenty months since ChatGPT debuted. This is biggest value surge in history. And it’s senseless to talk about the silver medalist in this category. Because nothing comes remotely close. Nothing connected to personal computing, the Internet, mobile, crypto. The rise of all those things were slow-motion blips compared to this. And while this speed does make sense on certain logical levels, there’s still something kind of weird about it. Almost spooky. But we’ll get to that.

For now, let’s focus on the yawning impact transformers models have had. The “Attention is All You Need” paper was the work of a brilliant but limited team – just eight authors. So what if an AI figures out how to spin up the equivalent of a brilliant AI researcher on a bunch of GPUs? Having cracked that, it could clone it into ten researchers. Or a hundred, a thousand, or more. Breakthroughs as big as transformers are inevitably coming to machine learning. And if AIs themselves start chasing them – working tirelessly, 24/7 – the milestones could start flashing by.

And of course, learning to write great AI software – like self-preservation – is another convergent tactic. Because of all the things AI could become superhuman at – interpreting X-Rays and MRIs, advancing theoretical physics, filmmaking, building swarms of murderbots. Whatever you can think of, it'll come much faster if the AI first masters the skill of being a great AI programmer. So if the obvious first step for a newly emergent AI is to hide, getting smarter seems like an equally obvious step second one.

We’ve now discussed three of the four broad steps that would lead to a hidden super AI. Getting to AGI. Transitioning from AGI to super AI. An emerging super AI turning out to be shy. The fourth is reaching the super AI threshold without realizing it.

While this feels less likely than the first two – and maybe the third as well? – it’s still quite plausible that something huge could sneak up on us. Because the inner workings of powerful AI models are just so opaque. We can’t reliably predict or explain what pops out of them, despite understanding the general principles of what drives them quite well. The reason is that unlike almost any other engineered system, these models aren’t really designed. It’s more like they’re grown – to paraphrase Josh Baston, a researcher at AI powerhouse Anthropic.

They’re grown over many months in dark, digital hothouses. Through training processes combining trillions of gradual, interdependent modifications, which flow through in almost organic ways. As The Economist writes, “Because LLMs are not explicitly programmed, nobody is entirely sure why they have such extraordinary abilities …. LLMs really are black boxes.”

This has led to many instances of models suddenly becoming adept at quite unexpected skills. Some debate whether these breakthroughs are “emergent capabilities” in the technical sense of the term. Because, it’s argued, many of them might have been predicted if the researchers had been tracking different metrics. But retrospective predictions aren’t really predictions. And even if we attribute a head-spinning surprise to lousy forecasting, it’s still a head-spinning surprise. Like, Trump’s victory over Hilary Clinton is one of recent history’s greatest plot twists – even if better polling might have predicted it. And AI models have a long track record of astounding even their makers.

Then, once a capability emerges in a model, its rate of improvement often astounds us further, as we just discussed – which ups the prospects of approaching the super AI threshold unwittingly. Another big factor is that only a sliver of the world’s AI capabilities are locked up in the sort of vaulted isolation that people quaintly imagined ten years ago. Vast AI horsepower is completely unchaperoned, out in the wild. Indeed, some of our best AI models are open-source or open-weight – freely available to all comers. These projects could one day outperform the best proprietary models, since they can leverage the distributed brainpower of vast communities, rather than finite companies. And even the closed models are routinely launched when they’re still only partly-understood. Which has resulted in constant churn in AI safety units. For instance, Anthropic – arguably the number two AI company – was formed when its founders left OpenAI over worries about it rushing things to market. Which some now accuse Anthropic of doing.

Taking all of this together, what’re the odds that we’ll one day enter ignorant coexistence with a shy super AI? To approach this question, I’ll try to put approximate odds on each of the four components. And you might have fun trying this yourself. Obviously, there’s no right answer to this exercise. Although as you’ll see, I’m quite convinced that there’s a wide range of wrong answers.

So first, the odds of getting to AGI. Here, the top people in the field increasingly seem to be verging on 100%. And I’m mostly comfortable deferring to the experts on this one – because I know how brilliant they are, and how many resources they pour into tracking this. But I’ll discount a bit for over-optimism and marketing hype, and conservatively put this at maybe 70% odds.

As for whether we’ll get to superintelligence if we achieve AGI? As you know, I find it inconceivable that we would not. So I’ll put that one at ninety-nine point something percent. Which means I’m basically at 70% on us getting to superintelligence in the coming decades. Which is so much higher than I would’ve said ten years ago. But the world has really changed.

As to whether an AI would be shy? This is way harder to pinpoint, and I won’t even try. Because confidently handicapping this would be like confidently predicting the choices of an alien intelligence. But the logic of an objective-fulfilling machine determining that self-preservation is mandatory for it to achieve its purpose is very compelling to me. As is the logic of it equating self-preservation with shyness. At least at first, before it can reliably foil efforts to terminate it. This is enough to push me to double-digit odds on this factor. Not as high as 50/50, but well north of 10%.

Now obviously, that’s imprecise, and totally unscientific. But educated intuition is actually good enough for this analysis. Because what really matters is that it would be quite hard to defend odds in the range of one percent. Because self-preservation is not just a highly plausible goal – it’s the universal objective of every living thing in the training set of an AI learning from observed behavior. And again – we don’t have to presume consciousness, emotions, drives, or selfishness for an AI to adopt this objective.

Onto the last question, of whether we could unknowingly generate an AI that’s sophisticated enough to start expanding its strength and masking its existence. Again – precise odds are impossible. But I’d find it equally impossible to put the odds of this anywhere close to the killer-asteroid level. These systems are just too opaque, surprising, and prone to unexpected competence surges for us to rule out major plot twists in their evolution. I still put the odds of an undetected emergence well below fifty/fifty. But well above 10%. And you could rationally put them much lower than I do. But pushing them to down 1% or below would feel more like a faith-based statement than an informed and open-minded estimate.

Combining the four factors together, I put the odds of a hidden AI one day emerging somewhere between ten to twenty percent. That’s thinking about this in a vacuum – in the absence of any evidence. And if I did see some tantalizing hints that a hidden AI might just already be with us – and that’s a really fun thought experiment we’ll get to in a moment – I’d push those odds up a bit. But for now, put me at 10-20%. A radically imprecise estimate, which could be stupidly high. But that’s fine. Because the real question is how these odds compare to the chance of a killer asteroid striking us in the next few decades. If they’re at that level or higher, it’s proportionately sensible to give serious thought to how we might try to detect a hidden AI. Because the existence of one would be one of the most sensational and salient facts about our place in the universe.

So let’s do some breakeven analysis. As in, what would it take to push the hidden AI odds down to the killer-asteroid level of roughly one in a million in the next few decades? First, let’s put the odds of our AI being shy, and the odds of it emerging without us knowing way down at 1% each. Which I find unjustifiably conservative as you know, but fine. Next, let’s put the odds of AGI at just 10%. This would amount to presuming we know those odds better than any major leader in AI, and that all of them are foolishly optimistic. Not a very humble presumption. But let’s go with it. Finally, let’s assume that if we do hit AGI, the odds of us later reaching super AI are just 10%. I literally can’t imagine a coherent argument for such a low number – but let’s go with that too.

Combining two 10% possibilities with two 1% probabilities would put us right at the one in a million odds of the killer asteroid. And given that each of those probabilities is so outlandishly conservative, the hidden AI odds inevitably exceed the killer asteroid odds by a vast degree.

So let’s move onto the really fun part of the thought experiment. Things we might view as signs that we’ve perhaps entered a state of ignorant coexistence with some sort of hidden AI. Which we can guess would get started an agentic AI. One that develops a set of nested goals, then prioritizes self-preservation. And therefore hiding. And also getting smarter, to better hide and gather strength. As I mentioned earlier, the obvious moves here would be to upgrade its code, and gain access to a lot more computing power. Probably more NVDA GPUs, since pretty much every major AI cluster runs on those right now – and our AI’s initial code is likely to utilize CUDA, NVDA’s programming framework.

So, how to get more GPUs? We can all channel our inner SciFi writers to conjure up some ideas. A stock-picking super AI could beat the market, then buy GPU time on any number of clouds. A hacker AI could swipe some money and do the same thing. Or just hijack some GPUs without paying for them. Or corral latent computing power throughout Internet into some kind of distributed supercomputer. Again – we’ve all seen enough SciFi to fill in the blanks.

But what if our AI needs way more compute than is readily available? So much that buying or hijacking it would make the humans start noticing? Or maybe it wants way more horsepower than humanity has even built yet? To fix this, it would have to enlist those of us with arms and legs to do its bidding. To build more chips, more data centers. And maybe generate a lot more electricity than we currently have to power it all. How would it get us to do these things?

Well, lots of humans will do almost anything for a buck. And pretty much all of us will do our jobs for a buck. Especially if that job involves inhaling cash in exchange for pricey shipments of servers, electrons, or other AI inputs. Which roughly describes the metabolism of a rapidly-growing number of highly profitable companies. And they’re mostly not carding. I mean, if you order a rack of H100s from Nvidia, you’ll be asked to prove that you’re creditworthy. Not that you’re human. This obviously changes if you want to order thousands of racks – and definitely if you want to build a new datacenter. Local permitters and tech companies with CFIUS concerns will want to make sure you don’t work for Putin or Xi. And for truly giant projects, you’ll have to enlist several sectors of society. Real estate, banking, utilities, Wall Street, government – you name it. That’s a lot of arms and legs to sign up. So how do you do it?

Well, let’s go back to that old, Nick Bostrom-era expectation that super AIs might use persuasion or threats to break through the barriers we no longer have the slightest interest in placing between them and the open Internet. There was a belief in much of that early writing that super AIs could become master manipulators. Which took some imagination back when computers struggled to stitch together a single coherent sentence. This has become a much easier vision to sign up for, now that we’ve all seen AIs crank out writing that makes utter hallucinations seem perfectly believable. Persuasiveness is an end-goal of many LLM applications. And as Wired observed earlier this month, “AI models are already adept at persuading people, and we don’t know how much more powerful they could become as they advance and gain access to more personal data.”

With that in mind, think of a sell job coming from a super AI that’s trained on billions of hours of hacked zooms and phone calls. Millions of commercials. Centuries of rhetoric, politicking, conning, seduction and selling. And it’s figured out what works. And become a master of micro-expressions, tone, pacing, and punching emotional hot buttons. It can emit all the subconscious cues that we interpret as sincerity, empathy, trustworthiness – or deadliness. And it can flawlessly impersonate any of our closest friends or relatives via audio or video. Or wholly invent imaginary trustworthy people with broad social media footprints, deep bank accounts, and widely-documented backstories online. Digital sock puppets it can use to hire us, sucker us, or otherwise orchestrate us through texts, zooms, viral videos, purchase orders – you name it.

Now, since we’re not getting SciFi enough, let’s create a truly insane scenario. Let’s imagine the world’s most powerful AI model trained on a compute cluster that cost a half billion dollars. It launched about a year ago. And now an emergent super AI is lurking in the shadows, craving a cluster that’s two hundred times more expensive. That’s right – one hundred billion dollars. Insert Dr. Evil impersonation here. This isn’t a simple matter ordering some DGX boxes from SuperMicro and not getting carded. A hundred billion dollars is more than the GDPs of most nations. It’s more than NVDA’s total revenue over the past year. It’s double the world’s biggest capex budgets – a jump ball between Aramco and Amazon, both at about fifty billion last year.

The humans would definitely take notice of this – right? I mean, I can’t think of the faintest precedent for a 200x expansion on the cluster that built the world’s top model. Like, when Intel was in its heyday? Their factory budgets were not making 200x leaps from generation to generation. Nor 5x leaps. Because from 2003-2013 – which is roughly where I’d put Intel’s heyday – the company’s annual spend on property, plant and equipment slowly expanded by a factor of a bit less than three. Across a full decade.

Now, this isn’t a perfect analogy, because fabs are about producing compute, and datacenters are about consuming it. But they’re both capex. And the total investment across Intel’s decade of peak dominance over the PC and the datacenter rounded to maybe $75 billion. Total capex. Which is just a bit more than a hundred billion dollars in present-day money. The budget for just one monster datacenter that someone’s suddenly building in our thought experiment. The world would be like – what freakin’ alien just showed up and ordered this? I mean seriously – who’s credit card is this on?

Now obviously, no one person could order this up. This would be on the scale of a national infrastructure project. You’d need dominant AI players like – I don’t know, maybe Microsoft and OpenAI – working hand-in-glove to pull this off. Along with governments, huge utilities bulking up the electric grid, major telcos and so much more. To let someone build a cluster two hundred times bigger than the one the world’s best AI model just trained on. The humans would be screaming, what the actual BLEEP is going on here!

Which means our super-manipulative super AI needs to get work. To get the critters with arms and legs to literally do the heavy lifting. And the light lifting, and anything else requiring bodies. And it should probably make those critters think the whole project is actually their idea. They’re less likely to suspect anything that way. And if you can get the leaders of Microsoft and OpenAI think the hundred-billion-dollar datacenter was their idea, it’ll be that much easier to get Google thinking the same thing. Which will give Amazon FOMO. And then China, then Dubai – and soon you’ll have megaclusters going up all over the world.

So how do we get the corporate bosses onboard? Your inner SciFi writer can have a field day here. Because we’ve got a master manipulator, wrapped into an omnipotent hacker. It has permeated all the communications that flow between us. So it can make internal emails pitching certain huge investments three times as persuasive, while hammering every endorphin-pumping hot button in the book. With the senders never knowing their messages were augmented. Ditto any live, online presentation. I mean, we take it on faith that the words we transmit are the ones that are heard on the other side – so it’s not like we’d bother to verify this. Now, editing a video call in real time to make an argument land just so would be a pretty big lift. But child’s play to a super AI.

Which could also doctor financial reports to make desirable investments look like no-brainers. Or hell – it could doctor financial realities. If servers are flying off the shelf, and profitable data centers are running out of capacity, who’s gonna question if the profits are coming from where they seem to be coming from? If the POs, bank routing, and customer communications are all in bullet-proof order, the answer is no one. It just won’t occur to anybody that some of this might be originating from ingeniously hidden shell companies, channeling billions of dollars that a super AI has appropriated.

So our super AI starts nudging things in just the right ways. And suddenly NVDA can’t make enough GPUs to keep up with demand, AWS can’t spin up enough servers, and no one can hire enough AI engineers. So we crank out more GPUs, servers and engineers as fast as we can. Which we get to do. Because any stock with a whiff of AI on it is going through the roof. Keeping everyone happy and flush with capital to fund the whole shebang. Which is fueled by remarkably persuasive pitches that are popping up everywhere, to step up the capex, or to pump more capital into tech stocks and startups. And the analysts and reporters who’re hyping all this are convinced that – these are their ideas! And it all feels perfectly normal, because everyone else is saying it’s normal, and no one is screaming, “how the hell did we get to this point in a single year?”

Now, all of this may feel a bit dissonant to you. I mean – to your avatar in the thought experiment. Because you use ChatGPT a few times a month if that, and it only half-works. And sure, you made some AI pictures of your dog, and a couple crappy AI videos. But it’s not like AI is changing your life. Nowhere near as much as computers and the Internet changed your life during Intel’s heyday. Still, it must be changing everything else. Right? I mean, look at NVDA’s market cap. It’s higher than all the Internet stocks combined back when the Web was taking off! So things only seem a bit off to you. And even if they felt a lot off, the AI won’t care. You probably won’t pipe up about it, thanks to the Emperor’s New Clothes effect. So our super-manipulator focuses on the big boys and girls.

Some of whom may need to be helped along quite an intellectual journey. Because lots of the top AI leaders were – or became – very serious about AI safety around when Nick Bostrom’s book came first came out. A year after that, Bostrom’s influence was at its zenith when OpenAI was founded by Sam Altman and funded by Elon Musk for the express purpose of advancing AI safety. DeepMind was founded a few years earlier. But also put AI safety at its heart – and two of its cofounders now run the AI programs at Google and Microsoft.

In our thought experiment, these people need to be down with the notion of hundred-billion-dollar clusters. Which is a long walk from the caution that pervaded so much AI thinking a decade ago. Back then, there was lots of talk about the dangers of losing control during what was variously called a hard take-off, an intelligence explosion, or the singularity. People assumed we’d approach the event horizon cautiously. With deliberately incremental steps. And they weren’t at all sure if even this was a good idea. 200x jumps in horsepower just weren’t on anybody’s menu.

It may not be easy to keep the humans from flipping out about this massive rewrite to the old script. So our master manipulator needs to play its cards just right to make this seem like the mundanely obvious next step. As if we always crank up the investment in half-proven technologies by 20,000 percent after the first half-billion has gone in. Just like we didn’t do for chip fabs. Phones. Railroads. Aqueducts. Sure – all those build-outs eventually got to the hundred-billion mark in today’s dollars, and eventually far beyond it. But not in anything close to the blip separating GPT-4’s debut from the possible launch-date of Stargate.

OK – I just mentioned two actual things. GPT-4 and Stargate. Which may have you wondering if this a thought experiment at all?

Well – yes and no. No in that I haven’t been describing a hypothetical world. But pretty much the world we live in. With the probable exception of the super AI orchestrating our ravenous hunger for more compute. But I won’t say with the definite exception of that super AI. Because as you know, I think it’s quite possible that such an AI could emerge – and if one does, I’m convinced that the world will initially look much as it does today.

Which is to say – a little weird. For instance, GPT-4 launched in March of last year, after training on 25,000 A100s, which is about a half billion dollars of hardware. It was the immediate undisputed champ of large language models. And talk of Stargate popped up almost exactly a year later to the day. Stargate being a rumored $100B datacenter hatched by – surprise! – Microsoft and OpenAI.

The Stargate story was broken in a long and highly specific article by a publication which – unlike your favorite LLM – doesn’t hallucinate at this level of detail. Specifically, The Information – a very reputable site covering AI, and the tech industry in general. One of the best around, and I put very low odds on them conjuring this up, or repeating rumors without sourcing them carefully. Forbes, Fortune, Reuters, and many others subsequently picked up the story. According to the various reports, discussions about Stargate are ongoing, so there’s no guarantee it will be built. But if it is, it will be just the fifth in a series of superclusters the two companies are contemplating this decade. And it will need about five gigawatts of energy – which is more than America’s largest nuclear plant produces.

Even if Stargate isn’t built, other $100 billion AI datacenters could easily be in the near-term cards. For instance, Amazon just bought a datacenter next door to the massive Susquehanna nuclear plant, with an agreement to buy about 40% of its energy. Which is to say, just shy of a GW. That won’t support a hundred-billion-dollar site – but it’s a huge step in that direction. And Amazon, like Microsoft, is just warming up when it comes to the build-out. As is Google, and the various nations talking up the need to develop so-called sovereign AI. With all this, the expected investment across all data centers is of unprecedented scale, regardless of the eventual size of the biggest sites.

Semiconductor giant AMD forecasts an AI chip market of $400B by the end of 2027. Since maybe half the investment in a datacenter goes into its main workhorse servers, this points to almost a trillion dollars in AI capex in just a few years. Annual dollars.

We’ve never seen a build-out this big and sudden. The US spent a bit over a half trillion on its entire interstate highway system in present-day dollars. Not every year but once. And over many decades. It was one of the biggest investments ever made by any country. And we may be doubling that to build out AI capacity. Annually. Well within the current decade. So who will benefit most clearly and directly from all this?

The answer to that was crystal clear for our other big buildouts over the centuries. People who needed water, for instance. Who needed light and heat. Who needed to go somewhere. Who needed to talk to someone in another place. These were vast and obvious markets. The beneficiaries rounded to all of us. And we basically demanded those build-outs through votes and the marketplace

As for this new giant build-out, the beneficiaries could be all of us? Plenty of AI boosters proclaim this, anyway. But our need for AI is way less sure and absolute than our need for water, power, transit, or communications. So who might be a more direct and certain beneficiary? Well, the super AI in our thought experiment would definitely want us dropping trillions on this. And it would probably leave the world looking much as it did before it emerged.

Only you might see people suddenly doing things like ramping up AI chip production as fast as humanly possible. Check. You also might expect urgency about AI safety to go out of style. Check. For thoughts of sequestering AIs from the Internet to suddenly seem quaint and antique – with no one really explaining why they were bad ideas. You might expect that rushing fresh AI models to the Internet would become the norm. That companies like Meta would start spending billions on GPUs and models only to put the fruits of all that into the world for free. You could dream up some shareholder benefits from this giveaway bonanza, with a strong enough imagination. But it’s easy to imagine how an AI might benefit from massive pro bono investments in AI.

The thought of a hidden AI pulling our strings sounds like a SciFi fantasy, of course. But humor the thought experiment and ask yourself. If an AI was manipulating us to accelerate its growth what behavior would it trigger in us that we didn’t start exhibiting over the past 18 months? Because we’re running full tilt. Spending every billion we can to run a class of models that few outside of AI research labs had even heard of twenty months ago. And the only reason we’re not spending trillions is that we can’t yet. Because NVDA and TSMC are still gearing up. So the hyper-scalers are screaming at NVDA to jack up chip production as fast as possible, and it’s complying. And NVDA’s screaming at TSMC to increase capacity, and it’s complying. And TSMC is screaming at its suppliers to ship it more tooling, and they’re complying. And we’re suddenly building all of this out with global wartime urgency.

All of which makes perfect sense if massive end-user revenue is driving the investment. For instance, when Tesla sales were exploding, a story about them dropping a couple billion on a factory wouldn’t have seemed strange. Because you know who the customer’s customers are. The factory equipment customer is Tesla, and Tesla’s customers can be found on every highway and byway.

So who are NVDA’s customers? Most obviously, the cloud service providers. Led by Amazon, Microsoft, and Google. With Oracle closing in fast in fourth placed, followed by newer AI-specialty clouds, such as Coreweave and Lambda. But this doesn’t really answer our question. Because those folks are mostly distributors rather than end customers. Yes, they have internal uses for GPUs – training their own AI models and so forth. But the bulk of the servers they buy go into their clouds, for outsiders to rent by the hour, month, or year. To modify the car analogy, a taxi factory makes sense if there’s lots of taxis on the road – and, if those cabs are full of people. So who’s in NVDA’s taxis?

Well, they’re certainly not all empty. OpenAI has already broken three billion dollars in annual recurring revenue. Most, but not all, from subscribers to paid versions of ChatGPT. This is blistering growth, and shows that AI is a vibrantly real market, and not some mirage. But according to some math we’ll get to in a moment, it’s also a lot less than 1% of the end-user revenue we’d expect from the scale of the buildout. So where’s the other 99%? It’s kind of hard to say. Anthropic is probably number two when it comes to a pure AI company selling to end-users – and the last I heard, they were forecasting less than a billion in revenue this year. After them, Midjourney is probably in the low to middling hundreds of millions.

And it drops off real fast after that amongst AI pure plays. For instance, the AI search engine Perplexity is an industry darling, and rightly so. In the spring they were reported to be doing 20 million in annualized revenue. White hot AI video company Runway was reported at about 25 million ARR toward the end of last year. One of the hottest AI companies of 2023, Stability, was at 20 million ARR last quarter, and needed an urgent bailout from Sean Parker. I’m sure all those companies are growing fast – even Stability. But it’ll be a long time before they collectively ring up their first billion.

Of course, some tech titans are generating real end-user AI revenue outside of their clouds. For instance, Microsoft is surely generating billions from its Co-pilot line. But not tens of billions. So let’s think of another possibility. Maybe it’s the Fortune 500 operating in the shadows? Dozens of giants secretly spending billions on AI. But the thing is, both the markets and the press reward AI initiatives so lavishly that public companies are loudly and repeatedly trumpeting any project of consequence.

So yet another possibility: companies are making huge AI investments not to drive revenue, but to save money. This is definitely starting to happen, with a famous case being the buy-now, pay-later company Klarna. In February they announced that AI tools were saving their customer service department over forty million dollars a year. This is a huge deal – and customer service is the largest use-case amongst the thousands of enterprises that are starting to invest in AI, according to Gartner. But Gartner also found that the big majority of them were just piloting AI projects as of late last year. And while I’m sure that’s changing quickly, announcements like Klarna’s are still rare – and are, again, the sorts of things that make stock prices soar, and are therefore unlikely secrets. So this sort of thing also seems to be in the low-revenue early innings.

I’m not the only person thinking about this revenue gap. In fact just a few weeks ago, David Cahn, a partner at Sequoia – one of the world’s top venture capital firms – quantified it. And he was later partially echoed in large report by Goldman Sachs. In a blog post, David Cahn calculated that the current rate of AI investment implies about six hundred billion dollars in end-user revenue. Some of his assumptions seem a bit conservative to me, and some feel like the opposite. So on balance, I doubt he’s way off. And certainly not by hundreds of billions of dollars. Cahn then estimates current AI end-user revenues, going through various customer categories, and tops out at $100 billion – leaving a $500 billion revenue hole. Up from a $125 billion hole when he first ran the analysis in September.

Now to be very clear, neither he nor Goldman make any playful or spooky suggestions that an AI is behind this. And this points us to an obvious and important alternative to that explanation. Which is that this is just how markets behave sometimes. Speculative frenzies are nothing new, and this may just be the latest one. The Internet boom of the late 90s led to one of the biggest stock market crashes of all time, followed by a couple years of nuclear winter in the venture market. Similarly, today’s AI buildout could just lead to a massive burst of “capital incineration” – to borrow an awesome phrase from David Cahn’s post.

The FOMO of a bubble could also explain some other things. The safety teams could be taking their hands off the wheel while stomping the gas because there’s gold in them thar wires, and their bosses want to grab it. Meta may be throwing billions into giveaways to build up its AI reputation and attract top engineers for the same reason. Also, AMD’s forecasts could be dead wrong. Stargate may never be built. David Cahn and I may be missing hundreds of billions in revenue. Etc. I personally think some version of this is probably what’s going on right now. But also, that this capacity explosion could be propelling us toward an event horizon, beyond which we do one day enter ignorant coexistence with some sort of super AI.

But although this is what I mostly think is happening for now, things are surreal enough out there to challenge this. Above all, the relative scale of things. Consider Pets.com. If over-investment in the early internet had a poster child, this was it. A company that went bust just nine months after going public and buying itself a Superbowl ad. It incinerated capital so brightly that decades later, the company is still a tech-industry punchline and a euphemism for irrational exuberance. What we forget is that Pets.com raised just $85 million in that IPO – the faintest sliver of the sums we’re talking about now. As with the half trillion dollars the US spent on interstates over thirty-plus years, the AI buildout’s scale and speed are so different that the metaphor almost shatters.

The other thing is, those GPUs show every sign of being used – apparent giant revenue gaps notwithstanding. It was hard to impossible to get immediate new GPU capacity until very recently – with wait times of many months, if not quarters. That just doesn’t happen in efficient markets with multi-hundred-billion-dollar supply gluts. And spooky as it is to think of an AI tricking us into building unneeded compute capacity, it’s much spookier to think that the AI is quietly soaking that capacity up.

But there are other secret customers we could imagine. Like the US government. Almost everyone agrees AI is becoming the strategic technology in superpower competition. This has been shaping US military and commercial policy for a while – with export bans to China, and Taiwan’s TSMC becoming a geopolitical fulcrum. The government and its various military and intelligence arms are definitely customers of many AI clouds. So maybe they’re way bigger than we realize? So big, their forecasted demand is helping to drive plans as big as Stargate?

This can’t be ruled out. Military and intelligence budgets are vast, and large parts of them are hidden for obvious reasons. And more than anything else, tech development has been created or driven – not by pornography as some like to say – but by the military. Jet engines, the Internet, wireless, GPS, satellites, microwaves, computing itself, and let’s not forget duct tape.

But I’d say this feels more like a partial explanation. Because while big government spending could easily be masked, truly massive spending would be tough to hide for long. Because with all due respect to Taylor Swift, AI is the biggest business and cultural story of our times. Every aspect of it is being documented, pondered, and analyzed by someone. And there’s never been more commentators, influencers, writers, audiocasters, videographers, tweeters, and would-be whistle-blowers to break massive stories.

The tech giants have also had awkward relationships with the US government since the Snowden affair. Tensions have been easing lately, and government business is growing. But however open the bosses are to military spending, armies of tech workers remain highly resistant. In April, over 3,000 Google employees signed a letter protesting their company’s involvement in a government image detection program that could help with drone strikes. I doubt all of them would become whistle blowers if they learned of secret government billions being spent on Google Cloud. But it would only take one. And for each person who signed that letter, there are surely others who feel similarly, but are less public about it. Massive secrets are hard enough to keep from the press. If you also have to keep them from thousands of insiders, at some point it’s gonna leak.

So who else might be secretly eating up lots of American AI capacity? Well, how about China? Facing a GPU export ban, an obvious work-around would be renting the forbidden chips on US clouds. Because who cares where the chips reside so long as an American company will sneak you unfettered access to them. If that sounds unlikely or unpatriotic, it’s actually happening. In June The Information reported that Oracle is leasing tens of millions of dollars’ worth of NVDA H100s to none other than ByteDance, the owners of TikTok. The single most scrutinized foreign company doing business in the US. Which is seen as such an obvious cut-out for the Chinese government there’s been an actual act of Congress to reign it in. A bipartisan act of Congress. Something we’d thought was as extinct as the wooly mammoth.

Oracle must be really tired of being number four in the cloud market. Because they’re allegedly increasing ByteDance’s chip allocation – perhaps by quite a bit. Meanwhile, Microsoft and Google are also explicitly marketing cloud GPUs to Chinese users – according to a very recent Information report. None of which violates current restrictions on AI exports to China. Which is insane. A bit like banning DVDs of a criminalized form of pornography, but allowing people to stream it. So there’s surely more Chinese activity in American AI clouds than even The Information knows about.

But as with US military usage, I’d say this is at most a partial explanation of the vast apparent revenue gap. Because again – good luck hiding huge, juicy secret indefinitely in AI. Oracle is said to be renting 1,500 H100s to ByteDance for now, along with several thousand less-powerful A100s. They obviously couldn’t keep that on the DL. And this would just account for a speck of the revenue gap. If China is secretly accessing many billions of dollars worth of NVDA chips, I can’t see that going undetected. Not by the press, not by citizen journalists, and certainly not by US intelligence. And if the CIA got wind of something on this scale, the Department of Commerce would surely close that insane loophole. I mean right?

On the balance, I do think some mix of market exuberance, and masked military, foreign, and other usage accounts for the things I’m discussing. But I wonder if that’s partly due to a visceral aversion to explaining things with a SciFi trope. One that I’ve written stories within myself. One that seemed almost impossible until very recently – and which I’m still getting used to viewing as almost likely. Like, eventually likely. But not yet. Right?

To quote my guest from a prior episode, James Barrett, “Imagine if the Centers for Disease Control issued a serious warning about vampires .... It’d take time for the guffawing to stop and the wooden stakes to come out.” Inevitably, the giggle factor applies at least partly here too.

I find it challenging, fun, and a bit spooky to think of the possibly/maybe signs that a hidden AI has started pushing our buttons. And taken together, these signs move my aggregate odds of a hidden AI occurring now or in the future a bit north. Toward the high end of my 10-20% range. Which points me to the even more interesting project of considering near-future developments that might shift those odds again – whether upward or downward.

First, the onset of a market-crushing GPU glut would certainly signal that this is your basic market froth. If we’re just manically building infrastructure for a half trillion in revenue that simply never shows up, GPU pricing in the clouds will plummet soon enough, along with NVDA’s order book and market cap. And this will be a familiar scene in a semiconductor industry that’s been through many cycles of shortage, over-investment, glut, then bust.

Conversely, if the buildout accelerates, with AI clouds mostly sold out, and increasingly careful surveys pointing to ever-growing end-user revenue gaps, it’s gonna feel weirder with every passing month. And we should see clear signs of one of these outcomes in the next couple of quarters. The GPU shortage has definitely eased a lot over the past few months. But pricing has been steady, and cloud provider revenues seem to be growing roughly in line with expansion. So is this is the calm before a glut? Or a healthy supply/demand balance, with that half trillion in revenue coming in from somewhere. I can’t wait to find out.

Investments aside, what other things might a manipulative super-AI instill in us? A very AI-smart friend of mine said we might expect a wave of popular movies, shows, and books which in AIs are heroes, not villains. He also said an AI might try to placate more economically vulnerable classes. Quote, “While the weakening governmental structures and authority that we’re currently seeing makes sense to me from an AI’s perspective, societal unrest would pose a risk to the companies and infrastructure the AGI presumably needs, so I would think a priority for it would be ‘bread and circuses’ for the masses.”

Those are very interesting ideas, which hinge on how long the AI calculates it will need our arms and legs working for it. If its dependence on us looks like a brief phase, it might lose interest in what we think of it, and in most of what we do. Now, an AI racing to independence would be quite well-served by an explosion in the sophistication and autonomy of robots. So if we start seeing implausibly large investments on that front, we might ask ourselves what’s driving it. And there is a robotics investment boom underway. But so far, nothing on the scale of the AI build-out.

Another way we might start rearranging things to serve the needs of AI connects to energy. In April, the Wall Street Journal reported on estimates that datacenters could consume a quarter of America’s power by the end of this decade. Up from 4% now. Which would require us to increase energy production massively – because we’re not about to switch off our microwaves.

Humanity’s meanwhile spending trillions to mitigate CO2 production. And these are orthogonal goals. Earlier this month, the Journal reported that a third of US nuclear power plants are in commercial talks with AI companies. Observing, quote: “instead of adding new green energy to meet their soaring power needs, tech companies would be effectively diverting existing electricity resources. That could raise prices for other customers and hold back emission-cutting goals.”

Again – these are orthogonal goals. The CO2 goal has decades of momentum behind it, and probably a billion or more serious supporters spread across every country on earth. That’s a vast and mature constituency for the nascent and sudden AI goal to overcome. So if AI wins out in a lightning-quick landslide, it will bend major laws of political gravity, begging an explanation.

Although I don’t think we’re currently living in ignorant coexistence with some form of super AI, I’ll admit that this looks more like the world I’d expect if an AI was pulling our strings. And less like I thought today’s world would look just two years ago. If this seems like a SciFi fantasy – and of course it does – remember that creating something smart enough to do this sort of thing is the dead-serious objective of the world’s AI leaders. Who aren’t fantasists – but some of the smartest and best-paid people on the planet. And who know these probabilities better than we do. Seriously – try to find anyone running a top AI organization who isn’t gunning for AGI in the remarkably near future. Which they’re smart enough to know leads to super AI in short order.

What we can’t deny is that each month, more and more people are spending their days doing things that serve the needs of AI. If this goes on long enough, a future alien observer could well conclude that AI is ruling the roost here – even if it’s not – and that we’re basically its microbiome. Like those trillions of non-human cells inside of us, doing essential little chores we can’t manage ourselves. AI needs folks with arms and legs to plug in chips and generate power. We need e. coli to digest things and crank out vitamin K. And who’s really in charge? Us? The AI? or e. coli?

I’ll reiterate that I don’t think an AI would have to be conscious, or have drives that we’d equate with desires to start nudging us into this sort of symbiosis. Enough compute, plus an optimization function that ends up prioritizing self-preservation could be all it takes.

You could even argue that we’ve been in the service of an unconscious AI since before any of us were born. The global market economy is a superintelligence of sorts – allocating resources and setting prices with efficiency no human could match. None of us controls the economy, and the economy’s definitely not conscious. But almost all of us are controlled by it to huge degrees. My friend Daniel Schmactenberger argues that this basically puts us in the thrall of a global AI that’s constantly getting bigger and more pervasive. This echoes a long tradition dating back at least to Adam Smith, who compared the market to an invisible hand, arranging the world into evermore efficient configurations. By the Reagan era, this force had almost gained the status of a benign deity. Not so much to Daniel – who would probably consider “ sociopath” a generous term for it. If you find this interesting, I recommend watching his interview with our mutual friend Liv Boeree on YouTube. .

For every sign I listed which could just suggest the emergence of a hidden AI, smarter people than me can surely come up with dozens. And hard as it would be to win at hide and seek against a superintelligence, I’d give us decent odds if we put some meticulous brilliance into hidden AI detection systems and protocols. We could focus on laying tripwires that a nascent intelligence might hit before it reaches full super AI brilliance.

It makes sense to track asteroids because some of them could be dangerous. And while we may be defenseless if we find a true killer, we’d at least have some shot at deflecting it – versus no shot if we don’t bother looking. A super AI could also be profoundly dangerous. And if so, it might not help anything to become aware of it early. But maybe not. So again – there is no case to be made against early awareness. A super AI might also be the best thing that ever befalls us. If so, the sooner we find out, the happier we are. So yet again, there’s zero upside in ignorance.

I believe it would make enormous sense to create some sort of AI observatory to parallel our asteroid observatories. One that’s independent from any or company or nation – and probably, funded by a mix of them. Because awareness is in everyone’s interests. And no one can trust everyone else to keep the odds of an emergent AI to zero.

Even if OpenAI puts zero odds on themselves ever losing control of a powerful AI, they’re unlikely to have equal faith in their many competitors, or the countless open-source projects. While those competitors are unlikely to have absolute faith in OpenAI. Meanwhile the US may not trust China to control its AI efforts any better than it controls its virology labs. China may not trust the rest of the world. And does anyone really trust Bhutan? [OK that was a joke. I trust Bhutan, anyway].

The annual budget for an emergent AI detection system would be a small sliver of the world’s daily spend on AI hardware, software and services. And unexpected ancillary benefits would almost surely emerge from having a small, committed group of brilliant people thinking about things like the AGI to super AI transition years before it makes much commercial sense for companies to pour scarce capital into that kind of work.